Birds are everywhere, from the densest of cities to the highest of mountains, the driest of deserts to the deepest of forests. They are spread across Florida, the country, and the world, and yet their true nature can remain elusive. Birds are difficult to study, especially as they disperse away from their nesting grounds or fly hundreds of miles along migratory pathways.

American Flamingos

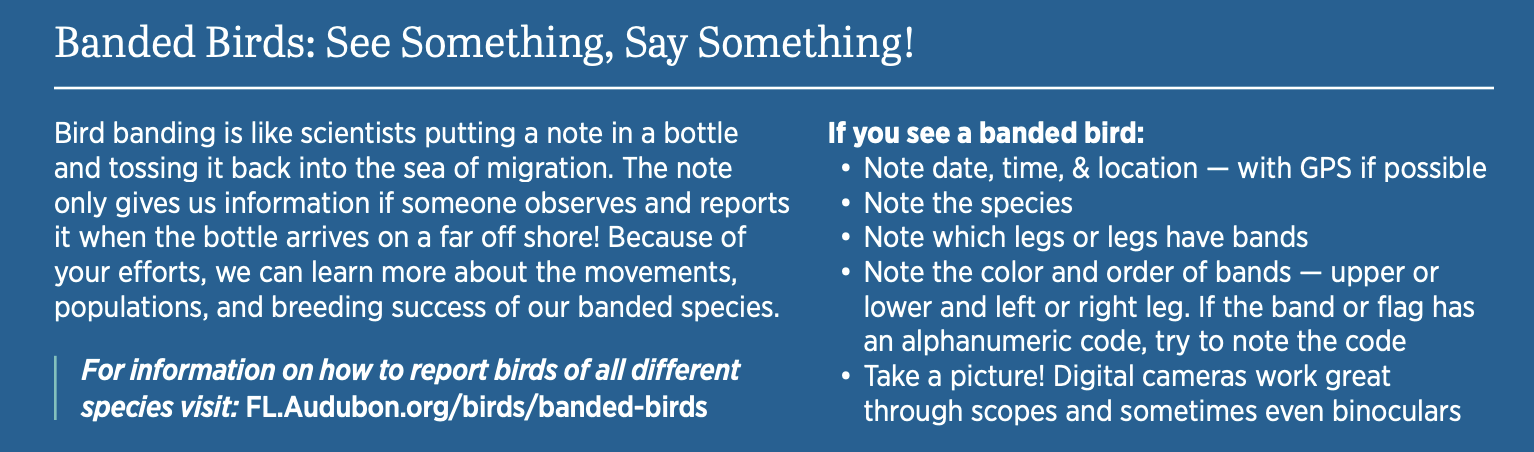

Flamingos are unusual birds that are practically synonymous with Florida, even though they are rarely seen in the wild. Over the past several decades, however, more sightings have led to new research.

Starting in 2015, Audubon Florida’s Director of Research Jerry Lorenz, PhD, took part in a study to determine the American Flamingo’s (Phoenicopterus ruber) natural history and habitat needs. Led by Steven Whitfeld (Zoo Miami) and other experts, the team afxed a tracking device to a young American Flamingo captured at the Naval Air Station at Boca Chica Key, Florida. The study tracked the bird, named “Conchy,” for nearly two years and reported on the bird’s whereabouts before the tracking device stopped transmitting signals.

According to the study, the flamingo spent much of its time around mangrove-fringed islands and mudflats at Snake Bight (Everglades National Park) within Florida Bay. The data showed that Conchy moved across the islands as prey became available, but did not leave Florida as many anticipated it would.

Findings from the study can help guide management strategies for Florida Bay and surrounding regions with ramifcations for flamingo conservation in the future.

Florida Grasshopper Sparrows

Florida Grasshopper Sparrows (FGSP) are dependent on the dry prairie ecosystem of central Florida and found nowhere else. Some 90% of Florida’s native prairies have been plowed under for human uses, but three large conservation areas, the Three Lakes Wildlife Management Area, the Avon Park Air Force Range, and the Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park, have high quality habitat and have been managed specifcally for sparrows. Back in 2000, the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow population at Avon Park dropped from about 150 singing males to ten in only four years. The Kissimmee Prairie followed next with a long decline; Three Lakes was last, as 140 singing males in 2008 declined to only 34 by 2019.

In 2020, we reintroduced the frst captive-reared sparrows to the wild and they not only survived, but also nested and successfully fledged chicks. Three Lakes WMA, the area with the most sparrows remaining, had at least 89 birds this year, with 35 documented breeding pairs. This is almost twice as many as before the releases started. At least 80 babies fledged from nests in 2021. The DeLuca Preserve had at least 17 singing males and is a candidate for new releases in the coming years.

The bands help researchers follow the family trees of these sparrows, to monitor breeding success of captive-reared versus wild sparrows, and track how their offspring fare over time.

The reason for the sparrows’ decline remains unclear. Is it disease, low nest success, low annual survival, habitat management problems? Captive releases buy us time to resolve underlying issues driving declines.

Roseate Spoonbills

When early conservationists established Audubon’s Everglades Science Center (ESC) in the Florida Keys in 1939, staff began Audubon’s 75-plus year history investigating the spoonbill and its environment.

Roseate Spoonbills have gradually recovered and have established new nesting colonies in South Florida, in the Tampa Bay area, and along central Florida’s Atlantic coast. Now, according to new research by Dr. Lorenz, spoonbill nests are shifting to escape habitat destruction in the Keys, as well as poorly timed water releases in the Everglades. In 2009, the “pinks” became one of 13 indicator species recognized by the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Task Force within the Everglades Restoration Plan.

In 2003, Audubon Florida began applying leg bands to chicks in nests in Florida Bay and Tampa Bay at the Richard T. Paul Alafia Bank Bird Sanctuary (leased from and managed in collaboration with The Mosaic Company). In 2013, the team began banding birds that hatched from nests at St. Augustine’s Alligator Farm; in total, we have banded more than 3,000 chicks. Banding spoonbills has led to a greater understanding of dispersal rates and behavioral structures after nesting season in the Florida Bay is over.

In 2021, researchers added satellite trackers to a handful of spoonbills, leading to the discovery of previously unknown nesting areas. This data will also indicate how Roseate Spoonbills will be able to handle climate change and how the birds are affected by sea level rise.

American Oystercatchers

Lanark Reef is a two-mile long string of sandy vegetated islands surrounded by marshes and mudflats. During low tides, the site grows in size as the drop in water level exposes a vast expanse of sandbars and seagrass beds that are perfect for foraging shorebirds and roosting seabirds.

While there are a large number of shorebirds and seabirds at the site, the high number of nesting and nonbreeding American Oystercatchers is the primary reason for ongoing protection of Lanark Reef. In 2021, Audubon Florida staff counted 13 nesting pairs of oystercatchers, and during the winter, we documented over 120 nonbreeding American Oystercatchers, making Lanark Reef a location of international importance to shorebirds.

The 2021 breeding season proved successful, with all nesting species fedging chicks. For the frst time in nine years, a flight-capable American Oystercatcher chick successfully fledged and was documented at another site. How do we know? The bird bands!

Black Skimmers

Black Skimmers are one of the most striking birds on the East Coast: These black-and-white birds with the massive, underslung, orange lower jaws cruise the waters of beaches and back-bays from Florida all the way to Maine. However, for all of their conspicuousness, researchers did not know how far skimmers traveled during migration, if they returned to the same nest year after year, how they picked mates, or even how long they typically lived. All that has changed with Black Skimmer banding programs led by Audubon and partners, and the information we’ve learned has profound implications for skimmer conservation going forward.

The programs, the first of which began in partnership with Dr. Beth Forys of Eckerd College in Tampa Bay in 2015, have spread across the Atlantic Flyway. Projects in Florida, North Carolina, New York, and other states all attach tags to skimmer chicks that anyone with a good pair of binoculars can read and then report back to a central database.

We have already learned so much. For example, Black Skimmers spotted at Clam Pass in Collier County in mid-winter include birds banded in FL, NJ, NY, NC, VA, and MA, which highlights the importance of Florida’s Gulf Coast beaches to skimmers from as far north as New England.

Least Terns

Least Terns are small seabirds that nest throughout much of the continental United States during the summer months before migrating south for the winter. While historically they have nested in mixed-species colonies directly on sand, human development, disturbance, and increased predation have sent many to gravel rooftops, which resemble their preferred habitat while protecting their chicks from on-the-ground dangers. Audubon staff both monitor the rooftop colonies and install fencing to prevent as many chicks from falling of the roof as possible.

However, since banding began, we have learned that these baby birds are surprisingly resilient — the majority of chicks that fall of of their rooftop nesting sites actually survive to fledge. Moreover, baby terns born in these rooftop colonies can go on to nest on beaches or roofs, and do not necessarily choose to nest on the sites where they were born. In fact, once a colony breaks up, birds disperse to diferent beaches and wintering grounds.

Critical information on rooftop Least Terns has taught researchers that these colonies not only produce fedglings for future roof nesting, but these individuals also join colonies up and down the Florida coastline. Put simply, protecting the roofs protects an important breeding pool that can pump up beach-nesting colonies as well.

Bald Eagles

In July, Audubon Florida staff recorded the frst auxiliary band resight from the 2021 season! The Bald Eagle that we now know as Green K/48 was rescued on the ground near her nest in Orlando on April 21 and released on May 25. In mid-July, Nancy Barnhart and Steve Thornill spotted her again — perched hundreds of miles away at the Hog Island Wildlife Management Area in Virginia! Just a few weeks later, another eagle released in May was spotted and photographed by Wayne and Theresa Tyler when they visited Barren River Lake State Park in Kentucky, a bright green K/43 band on its ankle.

From 2017 through July 2021, Audubon has banded and released 70 fedgling Bald Eagles as part of an ongoing study to determine eagle nesting habits. Do eagles that hatch in artifcial structures return to similar infrastructure when they build a nest? Or are they equally likely to choose a tree for their nest? Is nesting becoming more common on artifcial structures?

“Banding resights like this one bring us one step closer to understanding the future of Bald Eagle nesting habits,” explains Shawnlei Breeding, Program Manager for Audubon EagleWatch, “We depend on community scientists to help us track these majestic birds.”