Baby season at the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey’s Raptor Trauma Clinic is the busiest time of year. Fledgling raptors arrive in droves, and Clinic staff work around the clock to treat injuries and illnesses and return as many babies as possible back to the wild. Cameron Couvillon is the Center’s seasonal raptor care assistant, brought on during these busy months to help with the testing, treatment, and feeding of the many patients. But when the last patient has been fed each day, Cameron is working on a mind-bending project that could have a lasting impact on the treatment of raptors in the Raptor Trauma Clinic.

Beginning the Journey

Cameron began his Audubon journey as an intern in May 2021. After graduating from Florida State University with a biology degree, he was back in his native DeBary and looking for some hands-on animal care experience. He found it 30 minutes south, at the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey in Maitland. It was here, under the supervision of Clinic team members Beth Lott and Sam Little, that he learned to run labs, hand-feed, administer medication, and more. The following spring, he was hired for the seasonal role. With two seasons in the Clinic under his belt, Cameron noticed trends in the patients they were seeing, and he decided to investigate further.

The Raptor Trauma Clinic has an extensive database, with digital records of just about every patient going back to 1996. This data is housed in RaptorMed, a computer program built by Dr. Dave Scott at the Carolina Raptor Center to track patient data. Today, wildlife rehabilitation centers around the world use RaptorMed, and it has revolutionized the workflow at the Raptor Trauma Clinic. Every feeding, dose of medication, weight check, and observation is logged, and staff use the data to determine the next course of action for any given patient.

A Different Kind of Spark Bird

In the birding community, a “spark bird” is a species or individual bird that sparks one’s interest in the hobby. For Cameron, a bird sparked his interest in the RaptorMed data: earlier this year, a juvenile Red-shouldered Hawk arrived in the Clinic. While the bird was underweight, it had a perky disposition—a promising sign. However, over the next few days, the bird began to lose weight despite being fed four times per day and receiving additional fluids. The bird’s lab results weren’t promising either: both the PCV and TP levels were shockingly low. PCV, or packed-cell volume, is a measurement of red blood cells to white blood cells and serum, while TP refers to the total protein in the blood. The hawk’s PCV was just 14, falling well below the normal range of 30-50 and indicating anemia. The TP was just 1.0%, also well outside the normal range of 3.5-5.5%. After a few days, when the bird’s condition had stabilized, Clinic staff performed a blood transfusion, and the hawk’s condition improved.

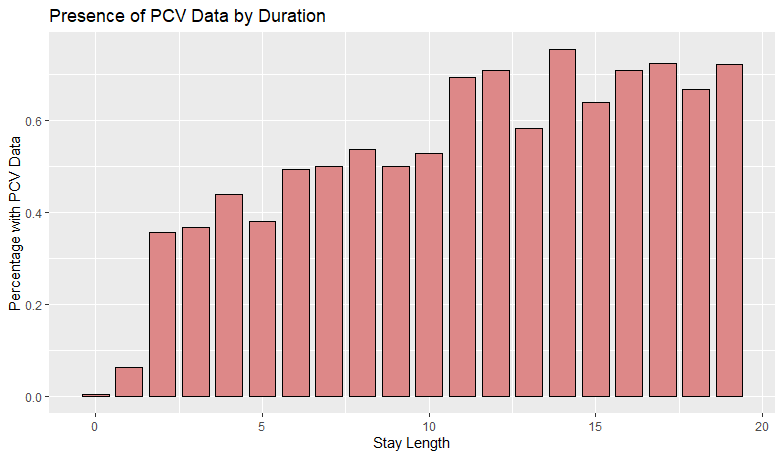

Curious about the correlation between PCV and patient outcomes, Cameron began looking at the data in RaptorMed. He began by defining a date range (2011-present provided reliable blood tests for most patients) and weight categories: good weight, thin, very thin, and emaciated. But he quickly encountered roadblocks: typically, when a bird comes to the Clinic, staff does not perform routine blood tests until the next day, giving the bird time to calm down from the stress of being rescued and allowing staff to treat acute symptoms that are immediately obvious. That means that the patients in the very worst of shapes, those who do not survive to day two, do not have blood test data for him to compare. According to Cameron, this gives the data a falsely optimistic slant, and it’s something he has had to account for. Roughly 3,000 of the 8,000 birds in his data set do not have bloodwork, either because they were healthy young babies when they were admitted, or they did not survive.

Data-driven Decisions

Through his research, Cameron has confirmed that emaciated birds have lower average PVC and TP levels than birds at a healthier weight. He continues to investigate how this knowledge can affect the care he and the rest of the Clinic team provide to birds. He says it’s the small decisions he wants to validate with data.

“The goal is not to write off birds with low values. Birds with very poor values can make a full recovery, and that’s always what we want,” he says. “My hope is that this data can influence smaller care decisions. For example, if a bird has low TP (total protein), perhaps we wait longer to introduce solid food. Should a bird go in an incubator, or should we just provide a heating pad? Right now, we’re making these decisions based on experience, but it would be cool if we could affirm our decisions with data, too.”

This juvenile Red-shouldered Hawk sparked Cameron's investigation into PCV and TP data when it arrived in the Raptor Trauma Clinic.

When his seasonal role ends in August, Cameron will stay on at the Clinic as a volunteer, continuing his research in his spare time. As for the Red-shouldered Hawk that sparked it all, Cameron had the honor of releasing the bird after its 31-day stint at the Clinic.

“It was honestly kind of magical,” he says of the release. “I found a small, wooded area with a little pond about a block from where the bird was found. After it had flown off, a few people from the houses nearby came and asked me about it. One of them thanked me, and another told me about a relative of theirs who used to volunteer at the Center. After how much I’d doted on that bird in the clinic, to see it sitting up in that oak tree, it’s the kind of thing that reminds me why I do this.”