It’s early on a chilly Tuesday in February as Audubon Biologist Jacob Zetzer bundles up and readies for his day: If the weather cooperates, he will be looking down on the treetop nests of Wood Storks and other wading birds at three known nesting sites in wetlands around Southwest Florida.

On the same day 150 miles away, Biologists Alex Blochel and Kevin Ramirez board a helicopter to access Audubon’s Everglades Science Center’s (ESC) water quality monitoring stations, which collect crucial data that guide state and federal policy decisions that can make or break Roseate Spoonbills’ nesting season.

Up, Up, and Away in Southwest Florida

As a member of Audubon’s Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary conservation team, Zetzer’s aerial surveys are critical for understanding the nesting effort and success for Wood Storks as birdy indicators of Everglades health. He checks the batteries in his camera, a donated Canon EOS 5D Mark III with a 300 mm lens, before hopping into a single-engine airplane — the flight is contracted through a local flight school and leaves from Naples Airport.

Zetzer conducts this important work each month from December through June, using his eagle eyes and camera to collect data throughout each Wood Stork nesting season. His reports include the bird species present at each nesting colony, number of nests, presence of eggs, stage of chick development, and confirmation, if possible, of birds successfully fledging from their nests.

Birds Tell Us About the Health of Our Wetlands

The combination of regional wetland loss, on the order of tens of thousands of acres over the last 25 years, and over-drainage of remaining wetlands in and near the Sanctuary has led to the near collapse of the Corkscrew Wood Stork colony that historically produced nearly half of the nation’s Wood Storks each year. Audubon investigated several potential causes and is working with regional partners to reverse the effects of over-drainage. Staff have also implemented a large-scale wetland restoration within the Sanctuary to ensure Wood Storks can continue to find the habitat they need.

In addition to wading bird surveys via plane, Zetzer also photographs the progress of the wetland restoration underway at the Sanctuary using a drone. After each drone flight he spends time at the computer, using GIS and machine learning to determine the plant species present, estimate canopy coverage amounts, and identify and count foraging birds in restored wetlands to guide further management action.

Monitoring efforts collectively paint a picture for Audubon managers to understand how Wood Storks are responding to habitat restoration at Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary. These data also contribute to annual nesting reports produced by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) and inform the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s management decisions affecting the federally Threatened Wood Stork population as a whole.

Getting the Water Right is Crucial for Roseate Spoonbills

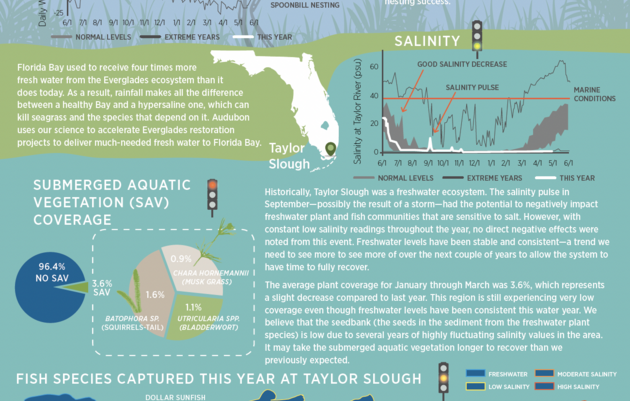

Deep in the Everglades, Blochel and Ramirez fly ten times each year to reach water quality monitoring equipment around Florida Bay. Audubon maintains a total of 23 locations with fully operational water quality stations—19 sites are only reachable by boat while four are so remote and difficult to access that staff rely on helicopters to get the job done. In close coordination with National Park Service pilots, the ESC team heads out early in the morning to take advantage of cooler temperatures and maximize daylight hours, spending about an hour at each water quality station on a good day, longer when they experience issues - timing of helicopter missions is vital.

Three monitoring stations are located within Everglades National Park, where Audubon works to understand changing conditions in locations that have been altered by dredging or channelization. In addition to servicing the equipment that continuously collects water quality data at the sites, Audubon staff also monitor control structure performance, check for evidence of saltwater intrusion, and ensure the devices are working correctly.

What Roseate Spoonbills Need

Roseate Spoonbills, which historically only nested in Florida Bay, are now nesting in other parts of the state due to changes in salinity and water depth. When the water where they forage is too salty due to reduced freshwater flows or saltwater intrusion, the fish community changes to mostly species that are either too large to fit in young spoonbills’ mouths or aren’t as nutritious. More importantly, water depth needs to be shallow —below 13 cm— for the birds to be able to forage efficiently because it concentrates the that spoonbills need for their growing chicks. Unfortunately, Audubon biologists are recording more of these high salinity and high water depth events in Florida Bay due to channelization and sea level rise.

Audubon is always adding new tools to our toolbox to understand how a changing climate and development in turn affect birds across the Sunshine State. The data inform common-sense policy solutions to protect vulnerable birds, like Wood Storks and Roseate Spoonbills, now and into the future.