On any given morning, a swamp buggy loaded with restoration gear lurches past an unassuming antenna mounted to a wooden platform that looks out across thousands of acres of wetlands in the Western Everglades. Here, it is almost impossible not to see birds. Some soar high in the sky while others take short hops from one patch of vegetation to the next. The number can be staggering, especially during migration when the resident population swells with birds seeking this habitat as winter destinations or as stopover points on their herculean journeys to and from breeding areas.

People have wondered about the annual reappearance of birds in their yards and gardens for centuries. Until recently, tracking a bird on its migratory path was a lot like finding a needle in a haystack. While technology has begun to unravel the mysteries of migration, we need to understand these movements now more than ever as human activities around the globe continue to reduce, degrade, or eliminate bird habitat. What we’re learning can guide land stewardship practices for the better—for birds, people, and the planet.

Ten years ago, Birds Canada established the Motus Wildlife Tracking System to tell us more about these migratory movements. The system relies on a network of powerful antennae with receivers that record data from tiny transmitters, called nanotags, that researchers attach to birds they wish to study. If the tagged birds’ migratory path crosses within twelve miles of a receiver, data from the tag, together with the exact time and date, is recorded and uploaded to a database on the internet where it can be accessed for analysis.

The National Audubon Society installs Motus stations in places like Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary in Southwest Florida as part of its conservation science program. The Motus network unlocks mysteries of migration and confirms locations that migrating birds need for survival, allowing groups like Audubon to prioritize these locations for conservation.

What Motus is Telling Us

In 2022, the Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary station joined the growing Motus network. The very first birds recorded by Corkscrew’s Motus station were Purple Martins, long-distance migrants that typically winter in the Amazon Basin after breeding across the eastern U.S. and Canada. Biologists at the University of Delaware conducted a study to learn more about their movement from the mid-Atlantic region and their breeding results, foraging habitat preference, timing of migration, and the locations where they roosted after breeding.

The University of Delaware team tagged 169 Purple Martins in June 2022. The Corkscrew Motus station detected three of those Purple Martins in early September. As the birds continued their southward migration, another station in Costa Rica picked up one of the Corkscrew-tracked Purple Martins. With the help of the Motus network, Purple Martins show us how they connect the dots between their habitats. Learn more about this study.

The 2022 fall migration at Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary continued through November and included a Bobolink, a Swainson’s Thrush, an American Kestrel, an Ovenbird, and a Gray Catbird.

Spring Migration 2023 – American Redstart

During the 2023 spring migration, a single bird pinged the Corkscrew station—an American Redstart on May 9. The Motus database indicated this bird was tagged in Jamaica as part of a long-term study investigating the connection between areas where warblers spend their winters, spring departure timing, and more. While some American Redstarts overwinter in Southwest Florida, visitors at Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary usually see them in spring and fall in the old-growth bald cypress forest.

The Georgetown University biology team tagged this bird on March 29, 2023, at the Font Hill Nature Reserve in Southwest Jamaica where American Redstarts have been studied since 1986. Their goal is to better understand bird health, winter habitat preferences, and how they fare in migration. The team is also monitoring long-term patterns of migratory behavior to learn how events and conditions the birds experienced during the winter affected them in later seasons.

The restart that pinged the station at Corkscrew, a male, occupied a territory in the high-quality, black mangrove habitat at Font Hill and was one of 115 birds tagged in the study. As it made its northward journey, a Motus station at Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge detected its tag just before the bird passed by the Corkscrew station. Nine days later, the next location that recorded its passing was at the Odessa Wildlife Station in Wapello, Iowa! According to the researcher at Georgetown, many of their tagged birds breed in the midwestern U.S., so it seems this bird safely made it to his summer home. Read more about their study.

Fall Migration 2023 – Red Knot

On August 6, the Motus station at Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary recorded its first migrating bird of the 2023 fall season: a Red Knot. Red Knots are long-distance migrants that breed in the Canadian Arctic. Each spring, they typically stop at locations from Delaware Bay to South Carolina to gorge on horseshoe crab eggs before completing the long flight from wintering areas in the Southeast United States/Caribbean, the north coast of South America, the western Gulf of Mexico/Central America, or southern South America.

To learn more about Red Knots’ migration to their breeding grounds, Felicia Sanders, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources’ Coastal Bird Conservation Project supervisor, and a team of biologists tagged 40 Red Knots at Kiawah Island, South Carolina, on May 9, 2023. They specifically wanted to understand the birds’ northern route towards James and Hudson Bays to figure out where they stopped before reaching their breeding grounds each spring. The conservation of breeding, wintering, and stopover locations remains critical as sea level rise and commercial horseshoe crab harvest increasingly threaten Red Knots and other birds’ survival.

Data from the Motus network confirmed this Red Knot embarked on its northward journey from South Carolina on May 29. By May 30, it had passed by nine Motus stations in West Virginia, Ohio, and Michigan. After it passed a station near Lake Superior, the bird likely continued its northward journey to breed in the high Arctic. It was not detected by a station again until July 13, way up on the shore of Hudson Bay in northern Manitoba, Canada, after its breeding season concluded and southward migration was underway.

Sanders’ study showed that most of the Red Knots she tracked traveled north through the eastern Great Lake Basin without stopping, thus making the Southeast United States the last terminal stopover for the birds before breeding. Read more about this study.

This Red Knot evaded further detection until August 4 when it pinged a tower in Ohio. Over the next two days, it was recorded by stations in South Carolina and then Vero Beach before crossing Florida near the Corkscrew station. It has not been picked up by another station since August 6.

Did this bird reach its winter destination? We may never know, as the patchwork of Motus stations along its path is incomplete. The perils of migration, worsened by rampant habitat loss, resource competition, and climate change, confirm the need for more data in support of land conservation to curtail the loss of billions more birds in the coming lifetime.

Fall Migration 2023 – Barn Swallows

Between August 25 and September 1, the Corkscrew station recorded three Barn Swallows, tagged on June 26 by Jon Atwood’s team at Massachusetts Audubon to assess characteristics of foraging sites being used while nesting at Conte National Wildlife Refuge.

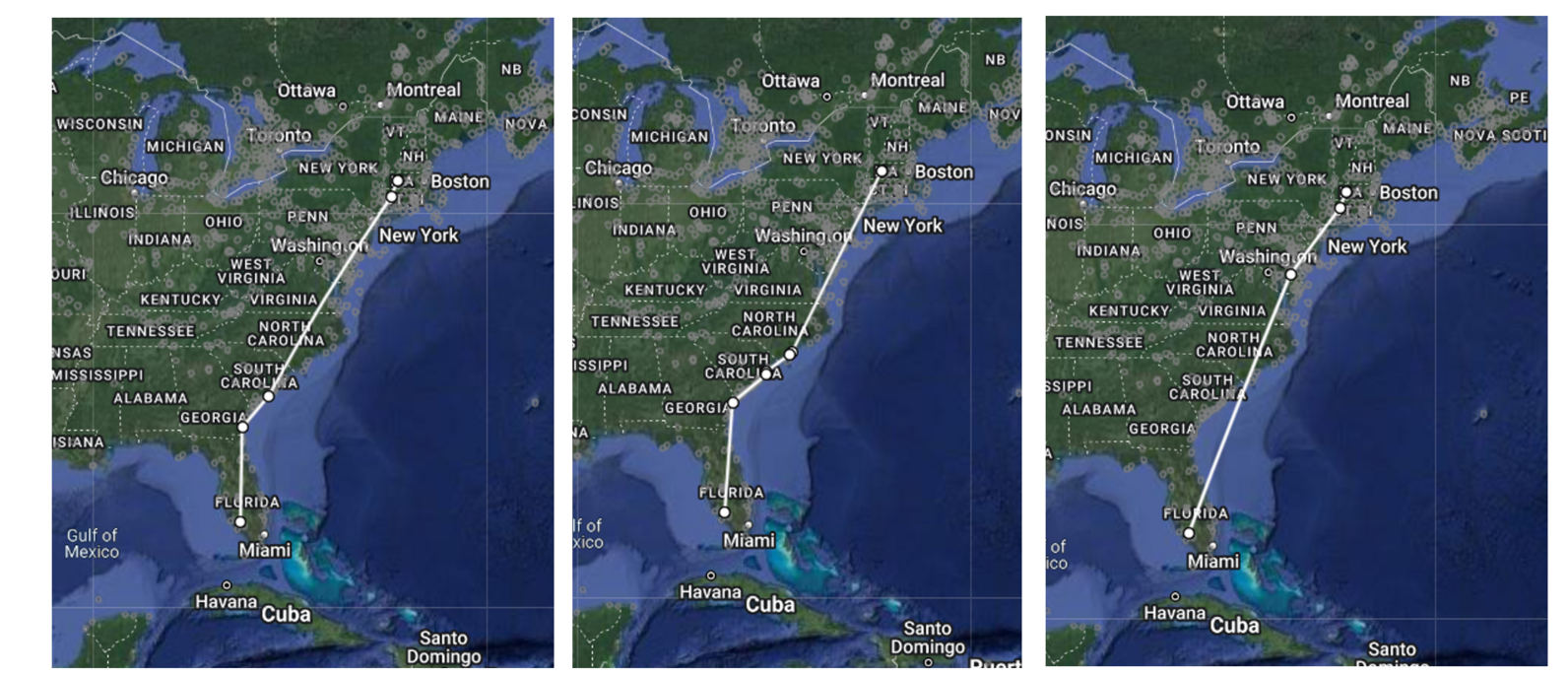

Barn Swallows belong to a suite of aerial insectivores that are showing serious population declines in northeastern North America over the past 50 years. Various causes of these declines have been suggested, including declining insect populations, industrial farming techniques that reduce the number of available barns for nesting, and mortality associated with climate change. These three birds, all of which originated from the same location, each took different paths along the Eastern Seaboard as they flew south, confirming that Barn Swallows’ stopover sites vary from individual to individual.

The Value of Tracking

The Motus Wildlife Tracking System is a tremendous tool for researchers and many others thanks to another new online tool, the Bird Migration Explorer, by Audubon's Migratory Bird Initiative and partners. This initiative combines the Motus data with information from many other sources to provide a guide accessible by scientists, land managers, and bird enthusiasts interested in learning about the migratory paths made by more than 450 North American bird species. The application even includes details about the many challenges birds face along the way.

Tracking migratory birds was once as difficult as finding a needle in a haystack. Today, modern technology – including the Motus network – makes it possible to monitor details about the timing and duration of migratory flights for birds of many species so that we can protect birds and the places they need into the future.

The data also inform land managers about birds’ seasonal habitat preferences, helping our staff learn more about the roles that places like Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary play as a stopover point or passage for migratory birds while filling knowledge gaps across the broader science community. The Sanctuary’s conservation team continues to restore wetlands that birds need to successfully overwinter before making the breeding journey back north in the spring.

What can you do?

- Be on the lookout for banded birds

- Report your sightings

- Volunteer as a Coastal Bird Steward

- Use your voice to protect birds and the places they need, today and in the future.